Blessed Mabon! A little late.

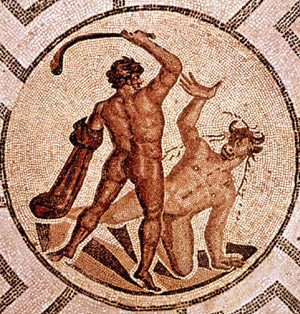

This is a good time of year to talk about the idea of the Sacred King and the Barley Man.

This part of the year, from Litha through Samhain, is focused on the young God and the sacrifice that will guarantee the continuity of the crops. The young god must die with this year’s harvest, and then enter the Underworld, so that he can be reborn in the crops of the following year. It is only through the sacrifice of the king that the people can flourish. Mabon (pronounced MAB-un) is at the center of this cycle.

Six weeks ago, at Lughnasadh, we celebrated the sacred games (named for Lugh, the Irish God of all skills). The winner of these types of sacred games is often crowned the king of the year, and at Mabon, the old king is sacrificed in a variety of different ways for the fertility of the fields. In some places, this is done every year. In other places, it’s either a three, four, five or seven year cycle. The seven year king cycle is found across multiple mythologies.

Looking across the wheel to Ostara, the goddess returns from the Underworld. At Beltane, she and the young god enjoy themselves together. Litha is when the sacred marriage takes place, and at Lughnasadh he is crowned king. At Mabon, the young God must die; and at Samhain, the Goddess travels back to the Underworld to be with him and start the cycle all over again (think of Persephone and Hades as an example of this).

In Wicca, we constantly celebrate the cycle of the Old God, the Young God and the Goddess. This is a cyclical mythology found across European mythology.

James Frazer talks about this idea in The Golden Bough, a book that you can read and reread over and over and still learn new things every time.

“IN THE CASES hitherto described, the divine king or priest is suffered by his people to retain office until some outward defect, some visible symptom of failing health or advancing age, warns them that he is no longer equal to the discharge of his divine duties; but not until such symptoms have made their appearance is he put to death. Some peoples, however, appear to have thought it unsafe to wait for even the slightest symptom of decay and have preferred to kill the king while he was still in the full vigour of life. Accordingly, they have fixed a term beyond which he might not reign, and at the close of which he must die, the term fixed upon being short enough to exclude the probability of his degenerating physically in the interval.” ~ Chapter 24, The Killing of the Divine King, Section 3. Kings killed at the End of a Fixed Term.

I actually came across this concept for the first time when in middle school I read Mary Renault’s The King Must Die . While this novel is historical fiction; it follows the life of the hero Theseus (famous for defeating the Minotaur in Crete) and looks at the transition from matriarchal society to a patriarchal one in ancient Greece. Reading this novel made me immediately think of Demeter and the rites at Eleusis.(I highly recommend this novel for anyone interested in this mythology. I read it when I was fairly young, but it is an adult novel with a lot of amazing mythological insights).

While Demeter searches for her daughter, She comes to the home of a human family.

And thus it came to pass that the splendid son of bright-minded Keleos, Dêmophôn,[25] who was born to well-girded Metaneira, was nourished in the palace, and he grew up like a daimôn, not eating grain, not sucking from the breast. But Demeter used to anoint him with ambrosia, as if he had been born of the goddess, and she would breathe down her sweet breath on him as she held him to her bosom. At nights she would conceal him within the menos of fire, as if he were a smoldering log, and his philoi parents were kept unaware. But they marveled at how full in bloom he came to be, and to look at him was like looking at the gods.[26] Now Demeter would have made him ageless and immortal if it had not been for the heedlessness of well-girded Metaneira, who went spying one night, leaving her own fragrant bedchamber, and caught sight of it [what Demeter was doing]. She let out a shriek and struck her two thighs,[27] afraid for her child. She had made a big mistake in her thûmos. Weeping, she spoke these winged words: “My child! Demophon! The stranger, this woman, is making you disappear in a mass of flames! This is making me weep in lamentation [goos]. This is giving me baneful anguish!” So she spoke, weeping. And the resplendent goddess heard her. Demeter, she of the beautiful garlands in the hair, became angry at her [Metaneira]. She [Demeter] took her [Metaneira’s] philos little boy, who had been born to her mother in the palace, beyond her expectations,—she took him in her immortal hands and put him down on the floor, away from her.[28] She had taken him out of the fire, very angry in her thûmos, and straightaway she spoke to well-girded Metaneira: “Ignorant humans! Heedless, unable to recognize in advance the difference between future good fortune [aisa] and future bad. In your heedlessness, you have made a big mistake, a mistake without remedy. I swear by the Styx,[29] the witness of oaths that gods make, as I say this: immortal and ageless for all all days would I have made your philos little boy, and I would have given him tîmê that is unwilting [a-phthi-tos].[30 But now there is no way for him to avoid death and doom.[31] Still, he will have a tîmê that is unwilting [a-phthi-tos], for all time, because he had once sat on my knees and slept in my arms. At the right hôrâ, every year, the sons of the Eleusinians will have a war, a terrible battle among each other. They will do so for all days to come.[32] I am Demeter, the holder of tîmai. I am the greatest boon and joy for immortals and mortals alike. But come! Let a great temple, with a great altar at its base be built by the entire dêmos. Make it at the foot of the acropolis and its steep walls. Make it loom over the well of Kallikhoron,[33] on a prominent hill. And I will myself instruct you in the sacred rites so that, in the future you may perform the rituals in the proper way and thus be pleasing to my noos.” ~ Homeric Hymn to Demeter, lins 233-274

She taught this little boy the mysteries of agriculture, how to sow and harvest the fields. While he didn’t end up being immortal, he was given a great gift, and is considered to be the founder of the Great Rites.

The greater rites were held in September and celebrated the Persephone myth. While whatever happened in detail at the rites is unknown, we do know that an initiation took place where those shown the mysteries came out with a greater understanding of death. Games and feasting were an important part of the celebration. Cicero wrote “Nothing is higher than these mysteries…they have not only shown us how to live joyfully but they have taught us how to die with a better hope”. (If you want to read further, I found this article).

In my coven, we celebrate the great harvest with a sacrifice of the barley man (called John Barleycorn in the British tradition). While the first fruits of the agricultural cycle are available around Lughnasadh, Mabon is when the fields are really ready for the first full harvest. At Samhain, we celebrate the final slaughter of the animals and the last harvest before winter comes. We send the Goddess off to the Underworld and turn inward for the cold months. But at Mabon, it’s time to celebrate the fruition of all our work throughout the year. It’s a time when we can fully reap everything that has been sown, both physically and spiritually. It’s a time for joy and celebration, but also time to sacrifice to ensure that the crops grow again next year.

While ancient cultures may have literally sacrificed the king, we are slightly removed. So we take the symbolic fruits of our labor and bake a Barley Man. I use gingerbread. Molasses, flour and brown sugar are all ingredients that are grown and produced here in Louisiana. Because we are ensuring the fertility of the cycle, he becomes a very obscene barley man, and at the height of ritual, we “chop” his genitals off and slit his throat. He is later left outside and offered to the Gods to do with whatever they will.

Feasting and celebration is a huge part of our ritual. This is our Thanksgiving. It is time to say thank you for the year that has past and start preparing for the year that is to come.

So feast and make merry and remember the sacrifice that goes into our lives. We may not be sacrificing the traditional way, but blood, sweat and tears still go into everything we have and do, and this is the time of year to celebrate that, embrace that and accept that sacrifice is necessary.